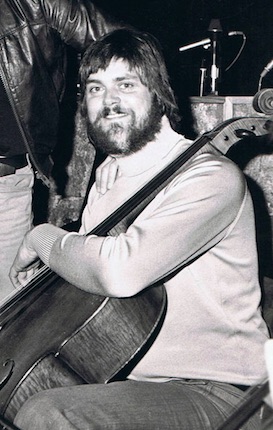

My dad in recording studio c1980

When pitching ‘Rachel’, it was easy to point to where the idea came from – a family Passover gathering in the Bronx, during which my mother-in-law Shirley provoked a heated debate about her future funeral arrangements by stating that she’d rather not have a whole load of fuss and that cremation would be her preference. And, of course, after causing much general outrage and emotional pleas for the rights of the mourners and their Jewish traditions to be respected, she was happy enough to finally shrug and contrarily declare “Eh, what do I care, I’ll be dead anyway?”

The situation made me laugh, but the underlying question raised was a serious one. “Who is a funeral for?” I’ve thought about it a lot in the course of writing and making Rachel.

My first experience of profound loss and grieving came when I was a young woman, just starting college, and my father passed away. Until then, one of my favourite episodes of Fawlty Towers was the one where a guest dies in the night and Basil enlists the help of Manuel to haul the corpse out of the hotel without anyone noticing. But, though I still find it hysterical, I cannot watch that scene now without an underlying memory of sitting with my mum and brother in my bedroom, and hearing the difficulty the funeral directors had in trying to carry my unwieldy 6ft 4in father out of our ancient, higgledy piggledy home via a balcony and a very tightly winding staircase.

That’s what I love about storytelling – whether on page or screen, the process doesn’t stop with the telling and, for better or worse, each member of the audience brings their own story to it.

When I watch ‘Rachel’ I recall the surreal experience of going straight across the road from my job at McDonalds to a funeral director’s chapel of rest on a busy parade of shops, where I sat by my father’s coffin while the whole world walked by uncaring of the sadness behind that door. I also remember discovering that, a few hours into the wake, my grandfather had hidden away the remaining scotch because we had organised the funeral my father would have wanted – a massive booze-up for all his musician friends – but my poor grandfather had lost his only child and, just as he had never really understood my larger than life dad, he also couldn’t understand partying as a response to his death. I think too of my first love whose ashes were scattered in the sea and my friend for whom there was no funeral and no opportunity for her friends to express the pain of losing such a vibrant and giving woman.

And, when I talk about ‘Rachel’, almost without exception, I receive a personal story about bereavement in return, and usually one about a conflict or trauma surrounding the funeral arrangements, which compounded the pain of that loss – a grandmother who had lived to such an age that there was almost no-one left to mourn her, parents who left a will to say that there should be no funeral, a deeply religious man forced to arrange a funeral for his atheist sister who had requested that everyone sing Monty Python’s “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life”.

The funeral director, whose premises I used for the filming of ‘Rachel’, had many tales to tell about families in conflict over arrangements or struggling with how best to represent the values, life and personality of a loved one. She felt it was really important for people to talk about this difficult subject and make plans before it’s too late, so she was very supportive of our project.

It does seem like a great way approaching things but, at the same time, part of me thinks that the process of grieving is actually aided by having to think about the person, about what they would have wanted. Is organising your funeral yourself robbing your family of an opportunity to work through and learn from the pain by expressing what you meant to them, just as one woman I heard from felt that she had been robbed of a chance to properly mourn by the way her super-organised mother had left the attic empty, all the paperwork in neat order and all her knick-knacks already despatched to charity shops? Rachel has been seen by very few people to date, but the predominant response has been satisfyingly positive:

“Brilliant”

“It’s lovely…very moving”

“Beautiful”

“Terrific, tough subject, really enjoyed it.”

And yet there is the one viewer who said she found it hard to connect with the characters’ grief and that the film posed more questions than it answered.

On the one hand that is a total failure – in my dreams she has just never experienced a loss that would give her personal access to this story but I may just have to accept that one truly can’t please all of the people all of the time. At the same time, however, I am glad to hear that the film posed more questions than it answered, for I did not set out to answer questions, merely inspire some thought and discussion on a very difficult subject.

I don’t have the answers. Just as my up-tight grandfather’s needs in grieving for his son could not easily coexist with those of a family that will forever mourn the loss of my gregarious, joke-telling, hedonistic dad, so ‘Rachel’ can provide no answers. The story is essentially a tragedy – every character is acting out love and a sense that they are doing the right thing, so whatever the outcome, someone will be terribly wounded. It’s the human condition, it’s history, it’s the reason hearts are broken and wars are fought and it’s why I wanted to make this film.